The Many Manifestations of Patriarchy in ‘The Great Indian Kitchen’ — The Social, the Religious, and the Cultural

This article is an in-depth analysis of the 2021 regional South-Indian Malayalam movie ‘The Great Indian Kitchen’ and It examines the socio-cultural and religious manifestations of patriarchy in the Indian society. I have approached and analyzed this movie using my mental models and some secondary research on subjects of menstruation and sex in the Indian society. Please note that this essay contains spoilers. If you haven’t watched the movie, I’d totally recommend watching it (link)—it also has subtitles for those who do not understand Malayalam. I have used several screenshots from the movie to make/support my arguments—they do not belong to me and are only used as a part of this study. Comments about religious Hindu customs and the Sabarimala controversy are my personal viewpoints.

The Great Indian Kitchen’ released in January 2021 has already been heaping laurels as the ‘movie of the year’ in India. This is not because it’s being pitted against the films that will come out later this year but because one so vocal has rarely made its way out in the past. The movie follows the life of a new bride who is married through arranged marriage to a teacher who comes from a ‘prestigious’ (a visibly upper caste) family. What ensues is the slow, creeping domestication of the wife within the confines of the home, ideas of the bridegroom’s family honour, and their traditions/customs. What’s particularly brilliant about this movie is how patriarchy is voiced at different decibels—how some of it is loud while some rather silent, some acts of patriarchy blatantly out there for the world to witness and some that’s normalized yet invisible, simply waiting to be seen. When I watched this movie for the first time, the screaming decibels of patriarchy stood out. Upon subsequent watches, the normalized, invisible patriarchy emerged.

This movie hit me personally. Unmarried as I am, I could still relate to this movie. I can see the many women and men from my own family and circle of friends playing the different characters in it. The eye for details in the visuals, the screenplay, and simple yet powerful plot of the movie works perfectly to tell us the age-old tale of the Indian woman. This movie applies to you, your mother, your great-grandmother, and all other matriarchs before them through a common thread called ‘patriarchy.’

You will notice the word ‘patriarchy’ brought up frequently in this article. Please note that when I refer to patriarchy, I am referring to the male domination of women in the public and private spheres of the society and the unequal power relationship between these two genders. I urge you, as you read this essay, to keep an open mind about ideas of patriarchy without associating the term to only extreme ideas of violence/oppression, thereby distancing yourself from the problem in hand. I say this because I truly believe we’re all a part of the problem. The characters in this movie are nameless—they are just referred to as father, mother, aunt, sister, wife, husband, and so on. The namelessness of the characters are indicative that you, me, and the rest of the society can be filled in for a name and the story will still work and make complete sense.

I know this is a long-form essay but I’d highly urge you to read this fully for it is important for us to have a conversation about what this film talks about. I’ve split this essay into three key sections:

The Dichotomies within the Patriarchal World of ‘The Great Indian Kitchen’: The Thematic, Sensory, and Spatial Dichotomies

2. The Many Faces of Patriarchy in the Men of ‘The Great Indian Kitchen’

3. The Women of ‘The Great Indian Kitchen’

1. The Dichotomies within the Patriarchal World of ‘The Great Indian Kitchen’

This movie showcases multiple symbolic portrayals of the unjust social and domestic situations women are all a part of, willingly or unwillingly. The common thread/thematic dichotomy that runs throughout this movie is regarding ideas of ‘purity.’ This higher-order thematic dichotomy manifests in some sub-dichotomies (sensory and spatial dichotomies) about which I’ll explain later on in this article.

The Thematic Dichotomy: Purity and Impurity

If you have seen the film, you have seen the mouth-watering dishes of a Malayali household. You see banana chips, puttu, sambar, avial, chutney, rice, etc.—it’s the stuff of your lunch dreams. The exuberant display of these vernacular dishes have often made its way into other movies where families dine together and there is a minute or two of screen-time of them eating, laughing, and making fun of one another—the family that eats together stays together, right? What then, about those who do the cooking of all that food?

Bringing the messy, dirty, and invisible labour women carry out to the forefront

This movie focuses on the representation of the before and the after of the ‘eating’ or just the general ‘being’ of a clean household. The time and effort that goes into preparing ingredients for a meal, cooking it, and then cleaning after is often invisible and unpaid labour that is not pictured in a lot of movies mainly because much of those stories are told from the male gaze and point of view. The cameras have finally panned to the woman’s point of view here—it shows the vegetable peels, dirty dishes, leaks, clogged drains, bad smells, and trash in the before and aftermath of a single meal that the men obliviously enjoy. The men often eat first and the women often end up eating last. When the mother-in-law asks her new daughter-in-law to have breakfast with the men on her first day at the household, the wife is shown to be uncomfortable. It innately occurs to be odd/wrong to her that she eats while her mother-in-law hasn’t and does all the work. It should strike a chord that the men display no such emotion. In fact, the husband (played by actor Suraj) cracks a poor joke/response:

“Fair, Mom too, needs company when she eats, right?”

Women usually do all the work in the kitchen , serve their guests/men and eat towards the end. This starts young in many families—note how even the little girl of the husband’s colleague and his mom were was going to eat later with his wife. Remember that gender inequality starts with your household.

If you are a man who wants to tell me that this isn’t a practice in your home, think again. Who does the traditional serving of the food, who makes sure your rotis/dosas come hot off the pan and into your plates? Who brings the dishes out to the dining table? How many of you feel even a tinge of guilt when you see your wife/sister/mother doing all of this work? How many of you help enough?

This sense of duty is usually instilled really early on for girls…even from the most ‘progressive families.’ When I was younger, I barely lifted a finger to help my mother properly much to my own chagrin right now. But with age, I grew into a different perspective. With that said, I was often guilted into being that person who wasn’t helping the women come an event or gathering, mostly by my patriarchal aunts, uncles, and even my own older male cousins. One can say that this was regardless of gender but I am most certain that those guilt-trips were constant reminders of me straying from the role my matriarchs traditionally performed…that any other identity I had outside as a gymnast, artist, athlete, orator, etc. was an addition to the identity I should ideally have inside the home.

When the women of the family finally do eat, they mostly end up serving the food for themselves. The men do not hover around serving them and in the instances that I have seen some men of the family do it, it was with a lot of talk and pride where they make light fun of the women they’re serving (think about all the sexist jokes uncles make about their wives and insert it here). Till date, I haven’t seen most of those uncles and cousins take on the role of serving me/other women food when I visit them, or cleaning the table after a meal (‘ecchal-idrathu’).

I, for one, hate ‘ecchal idrathu’—I don’t like using my hands for the task even now and go with a rag cloth. I have often heard older people in my family who used to say that one collects punyam (holy merits, if you will) when you clean the spot after a Brahmin completes his meal. Not only is it casteist, it’s also extremely sexist. I have not really ever seen a Brahmin man ever cleaning up after a woman’s meal in the traditional manner. But boy, do they pass comments about how the woman is supposed to do it (e.g., you should never sit down as you clean, you need to bend over to do it, and it needs to be done without ever lifting your palm/hand off the floor, so on and so forth). I’m not saying the men in the family don’t serve me food at all but that it’s a once-in-a-blue-moon event—it’s traditionally performed by the women in the family. Even then, most of the clean up is usually on the women’s shoulders…just like it was pictured in the movie when the husband’s cousin cooks for a night and leaves a battlefield behind for the woman to clean.

Women like me grow into our sense of duty either through tradition, guilt, or growing into adulthood. Men most often stay in their comfort space and enjoy the varying degrees of servitude they receive from their women, in many cases forever remaining a child who is spoon-fed every step of the way.

Ideas of ‘purification’ for the man and the woman

This whole movie has been set almost always within the large ancestral house of the husband and his family—a home that always seems to run smoothly and looks spotlessly clean. Symbolically, the large house in itself is representative of the family’s name, prestige, and its traditions…and the onus to keep it clean has almost entirely been put on the women of the household. Women take care of the home AND the family while the men take care of just themselves.

The most obvious and visible dichotomy that is seen throughout is the idea of purity vs. impurity—large notions of purity are usually associated with the male characters and ideas of impurity are associated with the women.

The men in the movie are often seen either cleansing their body/mind and dressed in clean crisp clothes whereas the women are represented with sweat-stained armpits and sticky clothes, cleaning themselves off of a day’s work at night

Purity of the body/mind: The men are often presented to be in the pursuit of something higher—cleansing either their body (ritual ablutions, brushing their teeth, etc.) or mind (yoga, reading the morning newspaper) at the beginning of the day. By good contrast, the women are shown wearing clothes that are stained with sweat; their depicted bathing or cleansing usually happens at the end of the day after all the domestic work is done…and it’s not something that washes off, in any instance. The wife obsessively washes her hand with soap to remove the rancid smell of food waste and other chores in vain. The only time she’s shown in an act of bathing during the day without thinking about the kitchen is when she’s asked to do a ritual ablution to purify her body after her period…well, no surprises there.

Purity in appearance: The men in this movie are usually portrayed rather crisply in their outward dressing, especially when they step outside their house (which is almost everyday) while the women dress down for their home. It’s particularly interesting to note the appearance of the wife over time. In the initial days at her husband’s home, she adorns pretty salwars and a few golden ornaments here and there—a few golden bangles, earrings, and her golden nuptial thread. With the progression of the movie, the luxury of adornments and ‘looking nice and presentable’ for herself takes the backseat for her in light of the work she has on her hands.

Purity of the intellect: While the men are frequently shown developing a world view (e.g., talking about the state of the society, teaching kids, etc.) and their inner world (e.g., yoga, going on a pilgrimage to Sabarimalai); the women are awarded no such luxury. The wife doesn’t have the time to practice her dance anymore and isn’t even shown attending her friend’s recital.

If as an Indian man, you think this isn’t true in your case…remember, it’s all about intensities of these practices. Think about the last time you went out as a family to a guest/relative’s home. Where were you sitting and what were you doing? Where did the women of the family automatically go? What were the men and the women of the family you were visiting doing? In short, who sat down to talk to you and who fetched you water or a cup of tea?

Sub-dichotomies of ‘The Great Indian Kitchen’

The Sensory Dichotomies

The director of this movie has done a tremendously good job engaging us through all of our senses and it has a kind of visceral effect on the viewer as a result. While I have included short descriptions about the most significant sensory dichotomies, I believe that the movie works as a whole in the tact through which they were all brought together,

The Visuals of The Great Indian Kitchen:

This film is shot with minimal outdoor shots. If you think about it, there isn’t a ton of visual variety in the movie…and it’s kind of the point. The repetition of the same spaces, the same kitchen, courtyard, bedroom, etc., brings a sense of voyeuristic familiarity in us, like you’re looking into the going-ons of your own home. The contrasting visual treatment of the spaces that are mostly inhabited by men and women is different, as well. Think about the dull, messy kitchen full of filth in which the women move about vs. the well-lit, spatial verandahs where the father-in-law/husband rest/do yoga at.

I remember at one point in this movie getting irritated and tired about the repeating frames of cooking, cleaning, and each day on end, again and again. And that’s when it really hit me…the movie does exactly what it set out to do. It gets under your skin in a way that you can’t turn away.

The movie shows a lot of trash and kitchen waste that the women of the household deal with everyday. In the larger symbolism of things, trash here is representative of the patriarchy women deal with everyday.

The Sounds of The Great Indian Kitchen:

Even as a person who loves a good background humming, music, or video songs as I am so accustomed to, I LOVED how this movie did away with background music of any sort. There is a boldness to not have any music that accompanies the stunning visuals of this movie. People don’t say too much either. The sounds of the movie mostly surrounds the shots of women with that of the routine chopping of vegetables, cleaning, mopping, scraping coconut kernels, the simmering of oil, the sizzling of the meat, the sounds of sex…you get the idea. The silence that surround the men is deafening—the morning chirps that accompany the husband doing his yoga, the silence in his classroom full of girls where he talks about ‘family,’ the monotonous ceiling fan creaking as the father-in-law sleeps during the afternoon…they all depict the luxury of not doing any backbreaking, unpaid work like the women do.

The sounds and visuals of this movie come together to allow us to fill in the gaps and experience mentally, the taste, touch, and smells of different situations.

The women are ALWAYS moving, doing something while the men have the luxury of a slow pace and rest.

The Pace of the Men and the Women

The men in this movie enjoy the luxury of slow pace and rest. Their women end up taking over most of the responsibility of the household. The men never have to actually lift a finger (think about how the MIL is shown handing over even the toothpaste and brush to her husband, how they don’t even wash their own plates…). The women on the other hand are always moving, running into each other, serving food, carrying out different housework and at the end of the day return to the bedroom to pleasure their husbands. Merely following the women in this movie makes me tired and my shoulders tight.

The Spatial Dichotomies

In the movie, the institution of traditions is represented by the stark contrast in the homes of the wife and the husband — the wife’s parents’ home is shown to be more modern indicating ideas of progressiveness in contrast to the age-old traditions of the ancestral home of her husband’s family.

A visual symbolic difference between the wife’s parents’ home vs. her in-laws’ home denoting intensities in progressiveness. Alternatively, they can also be viewed in the corollary as intensities of patriarchies within the two homes.

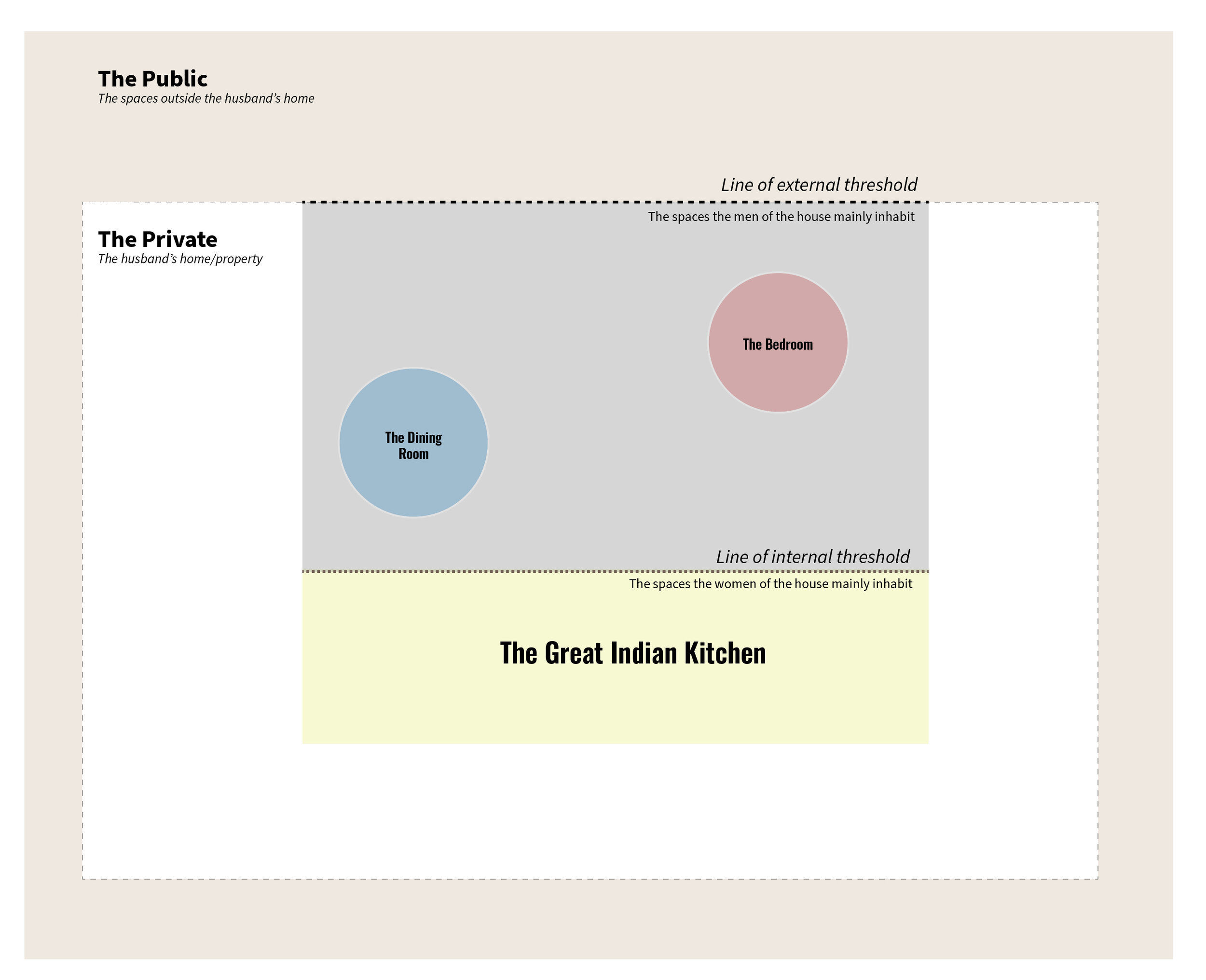

Most of this movie has been set indoors, within the four walls of the family home. It is very interesting to me that the director chose to portray the female point of view within the gendered space of the home, which is largely feminine (please read this article if you want to zoom out and learn more about gendered spaces). With a few watches of this movie in my belt, there was an interesting pattern in how the men and the women used the spaces of the large ancestral home. Here’s the visual spatial framework for the movie that will help me explain my thoughts on this further.

The spatial analysis framework for the movie.

While the movie is largely shot indoors, there is still a clear subdivision of gendered spaces even within the realm of the ‘private.’ Aligning with our everyday lives, men are largely shown inhabiting the semi-social spaces of the house whereas women almost always are shown in the kitchen or with a domestic gaze when outside of it.

Throughout the movie, men are always pictured in the entertaining spaces of one’s own home while the women gather in the the kitchen.

The gendering of spaces within the home can be illustrated using two ‘lines of thresholds’ as indicated in the framework above:

The Line of External Threshold: The Men’s Spaces

The way I interpret it, there is a clear line of external threshold that marks the entry to one’s home. The movie clearly illustrates how men are almost always in the public realm (e.g., school, temple, etc.) and how they assume the role of the family’s gatekeeper at the threshold to their home. They are either in the public realm or interfacing with the public realm. Women aren’t often shown at this threshold (except towards the end) depicting limited interactions with the outside world.

Line of external threshold: Men are shown to either be in the public realm or interfacing with the public realm.

The Line of Internal Threshold: The Women’s Spaces

The line of internal threshold on the other hand lies within the home. It interfaces with the more ‘social’ areas of the home that the men inhabit. Here, it’s marked by the threshold into the kitchen by the dining area. Almost 70% of this movie is shot beyond this internal threshold and in the kitchen.

Men are only shown to cross this space thrice—the husband is shown in the kitchen three times, both times right after his first night of marriage(s) and towards the end when he steps in, ready to assault his wife.

Notice how the husband is willingly shown in the kitchen only twice—the days after his first and second marriage. Also, notice how the composition has been set up to show the startling similarities between his first and second wife with key juxtapositions made visible showing the cycle of repetition.

The Crossing of the Thresholds

The climax of this movie culminates at these thresholds. While the spatial thresholds are more tangible, they hold a deeper symbolism of the gendered roles and spaces in the typical Indian setup. Towards the end, the wife crosses the line of external threshold to the home after locking her husband and father-in-law in the kitchen, when they are shown for the first and only time, crossing over the line of internal threshold to the kitchen.

Crossing of the thresholds: The men are ‘forced’ to cross the line of internal threshold to come into the kitchen to confront the wife while she ‘chooses’ to step out of her situation through the line of external threshold. This was a powerful, visceral and deeply symbolic moment in the movie.

The Shared Spaces of the Man and the Woman: The Bedroom

What makes this movie well-rounded is how it not only addresses the largely invisible and inherently subservient labour of the women in the domestic sphere but that it also addresses what happens behind closed doors in the bedroom. Women’s sexual needs and freedom aren’t addressed or acknowledged in the Indian society. Women’s awareness of their own sexual needs and desires are viewed as the mark of an improper woman while the man’s awareness is heralded to be ‘manly.’ I was recently going through some Instagram stories of a sex-education and lactation expert Swati Jagdish. It was shocking though not surprising to see how many Indian women haven’t had an orgasm in their life, even those who have birthed and raised children—sex has mostly been considered as a point of male pleasure and something that the woman has to endure. The movie has several shots that show how the wife feels discomfiture during sex and how the stench of the kitchen follows her to the bedroom, incessantly. She is clearly not having fun… not in the kitchen/home during the day nor in the bedroom at night. Uncharacteristic of a lot of Indian movies, the wife tells her husband that she wants more foreplay so she doesn’t feel pain during intercourse. The husband responds with intent to hurt her with his words—“I should feel something for you in order for me to engage you in foreplay.”

The man’s anger stems in her knowledge of the subject and his disregard for her sexual pleasure reflects an average Indian man’s ignorance and nonchalance regarding female pleasure.

Even during their first night as husband and wife, there is a certain awkwardness that’s showcased. The husband doesn’t talk to the wife or doesn’t seem to want to get to know her, her interests, or her wishes any better…nothing. Instead, he just asks her to “switch off the light” so they can have sex. It struck me how the pair are barely shown having meaningful conversations…just both of them going about their ‘supposed’ roles.

In my opinion, the husband is a Grade-1 Gas-lighter bordering on verbal abuse when he doesn’t get his way. The minute his wife exhibits some level of autonomy, desire, or independence, he lapses into accusations or excuses that makes her feel bad or makes her apologise for her thoughts.

The Shared Spaces of the Man and the Woman: The “Common” Areas

Outside the bedroom and the kitchen lies an expanse of an ancestral home which is almost entirely maintained by the women in the movie, as I had mentioned before. The chores in the house never seem to cease—the women are always cooking, cleaning, washing clothes, sweeping/mopping the floor, etc. The common denominator here are the women and the work to be done.

It’s ALWAYS THE WOMEN doing the work. If not for the mother-in-law, the wife did all the work. If not for the wife, the help/maid did all the work. If not for both of them, the aunt did all the work.

All throughout this movie, the man doesn’t lift a finger. Instead, he keeps bringing more women into the house to carry out all the work. (I’m going to add a few screenshots in the “The Women of The Great Indian Kitchen” section that illustrates this for your reference).

Where the Religious Meets the Socio-Political and the Domestic: Menstruation, Sabarimala, and more

Menstruation: An Inherent Act of Impurity

Menstruation is still an uncomfortable topic and a socially stigmatized subject in India. For some reason, we women are considered impure during our monthly periods. I’ve never understood how a sign of woman’s fertility and a normal human biological function could be a matter of such huge discussion.

Regressive practices and religious patriarchy surrounding menstruation are shown in this movie where the wife is asked to sleep separately, and not touch any bedding or clothes herself as she would ‘contaminate’ it. It goes as far as to even not show her face to the men of the family who are going to Sabarimala (a ritual pilgrimage for the Hindu deity, Iyyappan) as she’s not pure while the “swami” men are. It is irksome, these so-called traditions. While illustrated in the extreme in this movie, it’s not uncommon even in today’s modern India.

In a moment of complete honesty, my family…yes, my own parents believed and carried out these practices when I was growing up, though not as rigorously as shown in this movie. Growing up, I had to announce my period (with a ridiculous term in the Brahmin household called “Aathula Illa” or “out-of-the-house” // it relates to women living in the outhouse or separate quarters back in the day) and not enter the puja room and the kitchen of my house. I know of several upper-caste households within my extended family that still follow this. It’s embarrassing, infuriating, and downright humiliating, those three days. My father himself has been making ritual trips to Sabarimala for the past two decades and more; he’s a staunch believer in following all the rules for the pilgrimage. With time though, I rebelled and my parents ‘grew’ as we did. I had to go against my father and mother, my sister voiced her support and we don’t follow those practices now. If I visit my relatives now during my period, I don’t announce it anymore like I had to 15 years ago which a lot of my relatives still follow. I find it hard to accept the notion of a God who created me to consider me impure just the way They created me. It’s a weird concept— we all pray to female goddesses in faith, correct? You’re going to tell me that Shakti, the female cosmic force in this world in Her human form doesn’t menstruate? What do you all do, keep your goddesses outside her own room during her menstrual cycles?

To my fellow Indian men who clearly see these customs practiced in your households: I understand that a lot of times, it’s usually the older patriarchs or matriarchs who set up these rules. You grew up in these rules, possibly and it’s not alien to you, as a concept. During my conversations with fellow friends and family on this subject, I see a lot of men who say ‘I don’t interfere in these things’ as ‘progressive’ as they may be. Here’e my ask for you. Have you ever stood up for your wife/sister/mother in favour of not following these rules? How would you feel if I went around telling you what you can or cannot touch, and where to go in your OWN home? How would you feel about announcing a private, biological happening that nests in your groins? Do these questions/thoughts make you uncomfortable? Good. Now you know a millionth fraction of how we feel every time we have to announce our period like it was an impure disgrace on your world.

The movie does a great job in illustrating how humiliating these practices are and how this is likely because men didn’t understand the concept of menstruation. The husband is shown to be very uncomfortable when his wife requests him to bring her some sanitary napkins, an emotion shared by a lot of Indian men. While the wife’s mother herself doesn’t follow these customs (by virtue of her living in Manama), she stands by the customs wherever they’re practiced. The aunt, an enabler of these patriarchal practices harshly reprimands the wife for every little thing starting from her sleeping on a bed to her drying her undergarments out for ‘the world to see.’

The wife is required to sleep separately in a small room in the house during her period, forbidden from going into the kitchen or seeing the men of the family.

The Political and the Religious: The Sabarimala Controversy

The movie connects the personal, political and the social in a seamless thread. The woman in the domestic setting is subject to a lack of autonomy in her everyday life, even more so when she’s menstruating. The depiction of how such a private act is made so public, and how the wife’s character grows into her autonomy is very well done. It does feel a little disjointed in how it was annexed to a larger subject of controversy but, by and large, it’s successful in the weeds of it.

What I am about to voice are my personal opinions in the context of this movie and my life. My father makes this pilgrimage every year. I did, too, as a child, for three years. It’s among some of my happiest memories in my life and my father’s pilgrimage cohort still talk to me and treat me the way they used to when I was younger and made the pilgrimage with them. I love them for it. But as this issue stands, I am in agreement with the movie. I am not ‘willing to wait’ for me, as a woman to go to Sabarimala. As a spiritual person myself, I believe and love this deity and I don’t believe in the political-patriarchal angle to Hinduism that doesn’t permit women at this temple.

I have witnessed a lot of arguments from the Hindu community and my own social/family circles about how there are temples where only women are allowed and men aren’t…and I can take those responses in good faith. These are rules that have been put down long ago. Alright.

That said, who made these rules?

Who put the burden of purity and men’s celibacy on the woman? My bigger angst with this argument is that it’s a silo response to the Sabarimala controversy that completely passes over the larger standing concept of menstruating women not being allowed into temples during their cycles. There are a lot of arguments I hear from people who believe in this practice defending Hindu customs from a cultural point of view— that it is designed to allow women the rest from all the chores of the household.

I have two questions in response to that:

Why do you only want to ‘allow’ the woman rest during her menstrual cycle? What about all the other times?

If you are going to flaunt the idea of being respectful and giving the woman rest during a straining time of the month, how about you do that in a way that gives the woman her dignity?

I’m just tired of pseudo-scientific reasons that exist in our religion AND our culture. I am not saying all of our practices are wrong but that religious and cultural practices are subject to the century, caste and class dynamics, and times in which they were practiced. To change the context and not change the practice associated with the context is a logical flaw, in my opinion. There were no tampons and sanitary pads back in the day. We have some kind of access to those products now. Why are we unwilling to look at what the custom was trying to accomplish within the context in which it was set instead of blindly following the ‘rules’ with the turn of centuries? Why such a backlash to the women who choose to abide by their own rules and versions of what the religion/culture represents to them? Who made men the upholders of the religion to begin with?

This film shows a scene where the husband wants to make religious amends because his menstruating wife touched him when she helped him up after a small vehicular accident. He is shown speaking with his religious advisor who lists a few traditional practices that the pilgrim is supposed to take if they are ‘polluted’ by a menstruating woman. He then goes on to mention a simpler solution to counteract what’s happened. While I admit to not knowing the validity of the suggested practices, I second the irony of the traditions and customs for men changing with context and time. But what the woman has to abide by has been frozen in the yesteryears. A really telling scene was when the husband, furious by his wife’s behavior in the climax, removes his maalai before he attempts to slap his wife. It shows how in that moment, he didn’t give a damn about what the pilgrimage is all about (discipline and devotion to Iyyappan). All that mattered was that his position as the man in the house had been severely disrespected and he had to correct it.

2. The Many Faces of Patriarchy in the Men of ‘The Great Indian Kitchen’

This movie deals with a lot of trash—visually unappealing, viscerally disgusting and stinking trash. Trash in this movie symbolizes the institution of patriarchy which the women have to endure everyday. To clarify, this essay isn’t stemming from misandry but aligns with feminism in its stance against patriarchy. The term ‘feminist’ is often used as a derogatory term for the progressive woman in the Indian society (remember the term ‘feminazi?’). When I have conversations with men about patriarchy and feminism, I often hear two knee-jerk responses:

“I believe in the equality of sexes but not in feminism.”

“Patriarchy is far behind in the modern Indian society. I am not not patriarchal.”

My response to these parallel defenses align with the movie’s take on the depiction of patriarchy. As I had mentioned before, it shows the array of what patriarchy can look like in different intensities of practice. In a patriarchal society, men are inherently patriarchal due to the cultural and social power imbalance in the society. A man has to vocally be and undertake anti-patriarchal behaviors that has him shedding the comforts and advantages that he would otherwise benefit from in this society.

Oppression of women through violence, and oppression of women through elevation

The movie depicts different men displaying different manifestations of patriarchy as shown on the scale below. There are certain acts that are vocally patriarchal and frowned upon like the violent mob that attacks the home of the activist in favour of the Supreme Court ruling. This is classic oppression of a woman’s voice through violence. On the other extreme, we have normalized patriarchy where the woman is mansplained on everything. A perfect example of this is the father-in-law who ‘oppresses through elevation.’ What I mean by that is that he compares the family’s woman to goddess/ auspiciousness and her raising kids being as important as an IAS officer’s work. I have no shade for the homemaker but the FIL uses this kind of gentle, non-violent tool to suppress the women of the family and preventing them from going to work.

A question primarily to my Indian men: When someone says the word “patriarchal,” which side of the spectrum first comes to your mind? Did you think about the jarring and violent side? If you did, please know that you could exist on the other side of the spectrum. Patriarchal manifestations are a spectrum, not a singular act. By associating patriarchy only with extreme acts of violence, you’re likely being complicit on the other end. Please have an open conversation with your women friends and family about this to learn more about your own potential patriarchal behaviors.

The Women of ‘The Great Indian Kitchen’

The movie illustrates a lot of women taking on the domestic role for the household. Each of them do the household chores and fit into a role but with different intensities of patriarchy and awareness. I think the movie did a great job in showing the nuances of patriarchy that exists in women themselves, as a part of this structure. The director has done a great job of displaying the spectrum of women as seen on this scale of patriarchy enablers and patriarchy rebels.

All the women in the movie mapped on the spectrum of patriarchy based on how they 1. represent it themselves, and 2. respond to it.

The above scale is self-explanatory. The key takeaway is that women aren’t absolved from patriarchal practices. Most of us are complicit in this system, either willingly or unwillingly. There is, however, one character I found to be particularly interesting that I wanted to elaborate on—Usha, the househelp.

A Special Mention: Usha

None of the women in this movie have names. Always addressed as “adi” or “dho,” it was refreshing to see the house help, Usha, stand her ground and have a name. I think there are two possible angles to it:

Usha doesn’t have the ‘luxury’ of patriarchy practices as associated with menstruation and other ‘upper caste behaviors.’

She is probably one of the stronger characters who has an angle of empowerment through employment.

Even though Usha does all the work like the rest of the women in this movie, she’s the only one who stands to gain anything from it (i.e., getting paid for it). As the only named woman character in the movie who is not upper caste, she is shown freely singing and subtly going against norms of regressive practices with an easy-going attitude. The camera angles subtly show how she is different from the other women in this movie.

It’s always the women who are doing all the housework. Also, notice how Usha is always juxtaposed in a different direction to the other women pictured in the movie. I like to think it’s a distinction of class, caste, and autonomy that she has. While her lower caste causes her financial and societal disadvantages, she is pictured to have the autonomy that the upper caste women in this movie don’t have or come into.

The Evolution of the Wife (played by Nimisha Sajayan)

The wife in this movie is portrayed as the average Indian woman trying to balance her growing world views and trying to ‘adjust’ within the patriarchal setup which is norm. She isn’t explicitly shown as a rebel or proclaimed as a feminist. What started out as a surprise for her in her role with her in-laws’ family evolves to disgust, initial acceptance of the norm, hurt, anger, and finally, an informed break from the shackles of her married life. The story comes back in a full circle through dance and the bright red car symbolizing her journey over time.

The start and end of her movie is in her own red car…interestingly, we wouldn’t have even considered or thought about the fact that she could drive. Weird isn’t it? Also notice how she sits at the kitchen table in the climax, her nuptial thread clearly removed.

The movie has a lot of montage and short cuts that signify repetitive acts over time. However, there are two main long, follow shots in the movie that show the transformation of her character:

The last straw when her husband pushes her away in disgust when she helps him (after he falls off his scooter) because she’s menstruating, and

The final shot where she makes her way out of the house after locking her husband and father-in-law in the kitchen upon throwing filthy, kitchen waste water on them.

In the final scene (pictured above), minutes before she leaves her husband’s home, you’ll notice her sitting at the kitchen table almost fuming/deep in thought. By this shot, she’s already removed her nuptial thread that symbolizes her decision to walk out of the marriage. This shows intent and thought behind her decision and that it wasn’t just an outburst as many might assume (including her mother). I loved the little details that kept emerging with subsequent watches of this movie.

Ending thoughts

The Identity of a woman

This movie does a great job of showing the changing identity of a woman upon marriage. The director even does a great job of showing this aspect of identity through a series of shots that shows several framed photos of the husband’s forefathers—they’re all pictured as a family unit with children (ringing true with what the husband teaches in his sociology class). At the start of the movie, when the characters played by Suraj and Nimisha meet for the first time, there are several framed pictures on the walls as well.. but of her alone, individually, dancing… it’s such an interesting contrast that marks the differences in the her identity pre and post-marriage.

Pictured above are all the family photos in the husband’s home. Notice how in the bottom frame, you would notice several photographs of the wife as a dancer, and trophies next to Natraja on the shelves.

A closing visual remark lies in her final walk back to her parents’ homes where she crosses several houses where again, the men are shown resting on the vernadahs as the women work, a bus stop with Communist markings with men watching her on, and women in a tent voicing their favour of waiting until their menopause to visit Sabarimala. This, in my opinion, talks to the status of the women in the social, the political, and the religious realms.

Conclusion: This is your home, too.

It’s easy for us in 2021 to disassociate ourselves from patriarchy and misogyny, call our socio-cultural norms as ‘civilized’ and ‘equal.’ But our lives are resoundingly far from it. Patriarchy is pervasive and peeps its ugly head through all aspects of our lives. This movie did a great job in bringing out the many faces of patriarchy at the intersection of the political, personal, private, religion, and caste. I know there are going to be several people who are going to question the intentions of the movie due to a Christian director with a million what-about questions. If your knee-jerk is to protect that institution without reflecting how your everyday actions affect the lives of women, your questions and arguments are incomplete.

Please revisit the things you take for granted and reevaluate all the things you do as a man or a woman in this patriarchal society. Which of these are you trained to do vs. not? Which of these acts make your life comfortable while the other gender breaks its back? If you want to say you believe in the equality of genders, I’d start taking a long, introspective look at your own patriarchal practices. Peace!